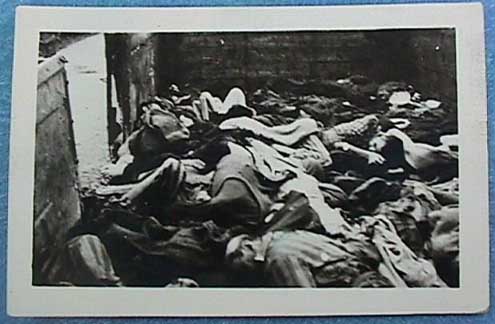

The photo above shows dead bodies on a death train

“The Mühldorf Train of Death” is mentioned in a recent news article which you can read in full at http://www.hattiesburgamerican.com/story/news/education/usm/2016/02/15/holocaust-survivor-speak-documentary-screening/80422828/

Young German boys were forced to look at the dead bodies on the train of death

I am not positive about this, but I believe that the train, that is mentioned in the news article, was the famous train that was found just outside the Dachau concentration camp by the American soldiers who liberated the Dachau camp on April 29, 1945.

I previously wrote about Dachau, and “The Mühldorf Train of Death” on my website at http://www.scrapbookpages.com/DachauScrapbook/DachauLiberation/MaxMannheimer.html

“The train of Death” at Dachau

The “lone survivor” of the Death Train

The following events preceded the tragedy of the infamous Death Train:

On April 4, 1945, the American Third army was advancing eastward through Germany and unexpectedly came upon the nearly deserted Ohrdruf forced labor camp near the town of Gotha.

Ohrdruf, which was a sub-camp of Buchenwald, was the first Nazi camp that any American soldiers had ever seen in Germany. Almost all the prisoners had been evacuated from Ohrdruf and had been taken to the Buchenwald main camp.

Like all the major concentration camps, Buchenwald had many sub-camps including one in a small town called Langensalza, where a former textile factory had been converted into a munitions plant which produced parts for Heinkel fighter planes used by the German Air Force.

On April 1st, which was Easter Sunday, 1,500 prisoners from Langensalza had been force-marched 60 kilometers to the Buchenwald main camp.

Buchenwald was already overcrowded with prisoners who had been evacuated from the camps in Poland, and there was no room for the new prisoners. In a few days, these prisoners from the sub-camps would be put on another train, the train that was to become infamous as the Death Train which so enraged the American liberators of Dachau.

According to the rules of the Geneva Convention, prisoners of war were supposed to be evacuated from the war zone, but this was not what had motivated the Nazis. They were concerned that the prisoners, if released from the camps by the Allies, would roam the countryside, attacking German soldiers and looting civilian homes, not to mention the fear of spreading the typhus epidemic that was causing the deaths of thousands of prisoners every day in the overcrowded camps.

The Nazis were especially fearful that Jewish inmates in the camps would exact revenge on the German people if they were released.

When the 6th Armored Division of the US Third Army arrived at the Buchenwald concentration camp on April 11th, 1945, the SS guards had already fled for their lives and the Communist prisoners were in charge of the camp. The prisoners were still locked inside the prison enclosure, but the gate house clock had been stopped at 3:15 p.m., the time that the Communists took over, and the camp was flying the white flag of surrender.

The American liberators promptly released some of the Communist prisoners and allowed them to hunt down and kill 80 of the guards who were still hiding in the surrounding forest. Some were brought back to the camp where American soldiers participated with the inmates in beating these captured German SS soldiers to death.

While the US Seventh Army was fighting its way across southern Germany, capturing one town after another with little resistance, the prisoners who had been evacuated to Buchenwald from the abandoned Ohrdruf forced labor camp were starting on their ill-fated journey which would end on a railroad track just outside the Dachau concentration camp. On April 7th, they were marched 5 kilometers to the town of Weimar. At 9 p.m. on April 8th, they were put on a southbound train.

The prisoners were guarded by 20 SS soldiers under the command of Hans Merbach. For their journey, which was expected to be relatively short, they were given “a handful of boiled potatoes, 500 grams of bread, 50 grams of sausage and 25 grams of margarine” according to Merbach, who was quoted by Hans-Günther Richardi in his book, “Dachau, A Guide to its Contemporary History.” According to Richardi, the train which left Weimar on April 8th was filled with 4,500 prisoners who were French, Italian, Austrian, Polish, Russian and Jewish.

It was unseasonably cold in the Spring of 1945, and there was snow on the bodies when the soldiers in the 40th Combat Engineer Regiment arrived on April 30, 1945.

According to Gleb Rahr, one of the few prisoners on the train who made it to Dachau alive, his journey had started on April 5th, when he was one of 5,000 prisoners who were force-marched to Weimar from Buchenwald. He had reached Buchenwald from the sub-camp of Langensalza only a couple of days before.

As quoted by Sam Dann in “Dachau 29 April 1945,” Rahr said that there were “60 open box cars” on the train and that “About eighty prisoners were forced into each car; thirty would have strained its capacity. Two SS soldiers were attached to each car.”

According to Rahr, after the open box cars were filled beyond their capacity, “Two or three (more) were jammed into each boxcar.” These additional prisoners were from one of the most infamous forced labor camps, the V-2 rocket plants at Dora, Rahr says. As described by Rahr, all the prisoners from Dora “were dying of starvation, and infected with typhus. Within a few days, every one of them had died. But the lice they had brought with them multiplied and settled on the rest of us.”

Rahr’s eye-witness account differs from the accounts of others: At first Rahr said that there were “60 open box cars,” but then he contradicted himself in the same interview, quoted in “Dachau 29 April 1945,” and said that there were “three trains of 30 cars each” which were bound for Leipzig. Another prisoner who was fortunate enough to withstand the trip on the Death Train and to make it inside the camp was Joseph Knoll.

Among the survivors on the Death Train was Martin Rosenfeld. He claimed that 350 prisoners were shot to death as they marched from the Buchenwald camp to the train station at Weimar, and that there were only 1,100 survivors out of 5,000 who boarded the train. According to his account, the train had arrived at Dachau on April 26, 1945, although Gleb Rahr and Joseph Knoll both told author Sam Dann that the date was April 27, 1945.

In his testimony before an American Military Tribunal in 1947, Hans Merbach said the train had arrived on April 26, 1945. The confusion about the date may have been caused by the fact that there were actually two trains that arrived at Dachau. One of them was parked inside the SS camp complex and it was empty.

According to Dachau author Hans-Günther Richardi, five hours after the train had departed from Weimar, Hans Merbach, the transport leader, was informed that the Flossenbürg concentration camp had already been liberated by the Americans.

The prisoners at Flossenbürg had been evacuated and were being death marched to Dachau. Many of these prisoners died on the way and were buried at the Waldfriedhof cemetery in the city of Dachau. The train had to be rerouted to Dachau, but it took almost three weeks to get there because of numerous delays caused by American planes bombing the railroad tracks.

The train had to take several very long detours through Leipzig, Dresden and finally through the town of Pilsen in Czechoslovakia. In the village of Nammering in Upper Bavaria, the train was delayed for four days while the track was repaired, and the mayor of the town brought bread and potatoes for the prisoners, according to Harold Marcuse who wrote about the train in his book “Legacies of Dachau.”

Continuing on via Pocking, the train was attacked by American planes because they thought it was a military transport, according to Richardi. Many of the prisoners were riding in open freight cars with no protection from the hail of bullets.

The final leg of the journey was another detour to the south of Dachau, through Mühldorf and then Munich, arriving in Dachau early on the afternoon of April 26th, three days before the liberation of the camp.

The prisoners, some of whom were not in very good shape to begin with, had been on the train for 19 days. Out of the 4,500 or 5,000 who had been put on the train in Weimar, only 1,300 were able to walk the short distance from the railroad spur line into the Dachau prison compound, according to survivors Rahr and Knoll, as told to Sam Dann, who wrote “Dachau 29 April 1945.”

The surviving prisoners on the train were barely able to drag themselves through the gates into Dachau. According to Rahr, the survivors were taken to the Quarantine Barracks and given “hot oat soup,” which he said was “the first food of any kind” that was given to them since the start of the trip. In his account of the trip, Rahr says that the only food the prisoners got for the whole trip was one loaf of bread on the first day. He mentioned the four-day stop in Nammering, but did not say that the prisoners were given any food, as claimed by the mayor of the town. Rahr told about the bodies from the train that were burned at Nammering. The burning was unsuccessful and the prisoners had to bury the bodies, according to Rahr.

By the time that the 45th Thunderbird Infantry Division arrived in the town of Dachau, the locomotive had been removed from the abandoned train and 39 cars, half of them with dead prisoners, had been left standing on a siding on Friedenstrasse, just outside the railroad gate into the SS Garrison. Inside the SS camp, another freight train stood on the tracks, but this one was empty.

Most of the Waffen-SS soldiers had left the Dachau Garrison on or before the 28th, leaving the food warehouses unlocked. When the news of the abandonment of the SS camp spread, the townspeople converged on the warehouses, looking for food to steal, just as the American liberators arrived.

The American soldiers were appalled to see residents of Dachau bicycling past the railroad cars filled with corpses, on their way to loot the warehouses, with no concern for the dead prisoners. After the camp was liberated, the Americans distributed the food from the SS warehouses to the prisoners, leaving the residents to fend for themselves.

Some of the dead had been buried along the way by the prisoners who had been forced to dig the graves, but towards the end of the journey, the bodies were just laid out along the tracks.

The bodies were left on the train for two weeks until the Army could do a full investigation. Tripods were set up near the train, and photographs were taken by US Army photographers. Soldiers who had “liberated” cameras from the Germans took numerous photographs and developed the film when they got home.

Young boys, who were members of the Hitler Youth, were brought to the train and forced to look at the decaying bodies. Boys as young as 12 were fighting in the war towards the end, so it is doubtful that these boys had any sympathy for the prisoners who had died on the train.

Nor did the residents of Dachau exhibit any sympathy for the dead prisoners on the train on the day of the liberation. A New York Times correspondent wrote about civilians looting the SS warehouses that were within sight of the train, while they avoided looking at the train and did not have the common decency to cover the naked bodies.

When the Death Train finally made it to Dachau, the sick and dying prisoners were left on the train along with the corpses of those who had died from exposure or starvation or had been killed when American planes strafed the train. One prisoner who was still alive on the day that the American liberators arrived was rescued.

According to Harold Marcuse in his book “Legacies of Dachau,” the wives of the SS officers who lived in the Dachau SS Garrison were forced to clean the box cars after the badly decomposed bodies were removed.

To get back to the news story, that prompted my blog post today, the following quote is from the news article:

Begin quote

Leslie Schwartz’ story of survival and freedom, captured in [the documentary entitled] “The Mühldorf Train of Death” will be shown at 6:30 p.m. in the University of Southern Mississippi International Center, room 101. German television produced the documentary on Schwartz, which focuses on his interaction with a group of high school students trying to learn about and honor survivors of the Holocaust. Admission is free.

Schwartz was imprisoned at age 14 near the end of the war and managed to elude death, but lost his entire family in the gas chambers at the infamous Auschwitz death camps. He will participate in a question and answer session at the screening. Earlier in the day, he will attend a pre-screening reception at Hattiesburg’s African-American History Museum and also share his story with students in a USM history class.

End quote

I have the feeling that Schwartz will not tell the story of the train accurately. How will he explain that he survived Auschwitz while his whole family was gassed? Children under the age of 15 were automatically gassed, according to the official Holocaust story, but Leslie was spared so that he could tell lies to future generations.