One of the regulars, who read my blog and frequently comment, is Dr.Wolf Murmelson, who was a prisoner in Theresienstadt when he was a child. Dr. Murmelson was the son of Dr. Benjamin Murmelstein, who has been criticized for allegedly co-operating with the Nazis, although he has now been exonerated.

I previously blogged about another child at Theresienstat at https://furtherglory.wordpress.com/tag/inge-auerbacher/

Dr. Wolf Murmelson always refers to his stay in Theresienstadt as “that Time of Darkness.” I did not get that impression when I went to Theresienstadt in the year 2000 and toured the town. After my visit, I created a website about Theresienstadt, including a page about the children doing artwork.

The following information is from my website:

Building L410 was a girls barracks and school where art lessons were taught

Shown in the photo above is Building L410, located next to the Catholic Church on Hauptstrasse, the main street of the ghetto. This was the home for Jewish girls from 8 to 16 years of age. The older girls, aged 14 to 16, had to work during the day, but still took classes at night.

The building also had a basement where concert practice took place. It was here that Mrs. Friedl Dicker-Brandejsova gave art lessons.

Theresienstadt was the designated site for the deportation of Jewish children from the orphanages in the Greater German Reich. Children were also sent to the ghetto with their parents or other relatives.

Approximately 10,000 children passed through the Theresienstadt ghetto. The drawings and paintings produced by these children in their art classes is known the world over. Some of their artwork hangs at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC. Many other Holocaust museums display their work also. The Jewish Museum in Prague has a collection of 4,000 pieces of children’s art from Theresienstadt.

Under expert adult supervision, the children were encouraged to express their feelings in their artwork. Some of the drawings that have been preserved show practice sheets where the children were obviously being taught the various elements of drawing.

The children depicted their surroundings in the ghetto in their drawings and watercolors, but they also painted what they remembered from their world before they were deported to the camp.

The drawings of the children were not censored by the Nazis, who allowed them free reign to express themselves on paper. Remarkably, the Nazis carefully preserved the children’s artwork after the children were deported to the death camp at Auschwitz.

Of the approximately 8,000 children who were deported out of Theresienstadt, only a fraction of them ever returned. Their paintings, which now hang all over the world, are a unique memorial to these innocent victims of the Holocaust.

Post office building which was formerly the children’s nursery

At the corner of Rathausgasse and Langestrasse, where the bus from Prague stopped, [when I visited the town in 2000] I photographed the building, shown above, that [was being used as the post office] in Terezin in 2000, but in the former ghetto, it was a home for infants. It also housed a pre-school and a kindergarten.

Some books [that I have read] say there were 207 babies born in the Theresienstadt ghetto, but others say it was 275.

All adults up to age 60, and young people over the age of 14, had to work in the Theresienstadt ghetto, so the infants and small children were taken care of in the building shown in the photo above, and returned to their mothers in the evening.

The building for the babies also had space for theater performances in the evening. In addition, there was a bakery and kitchen which supplied the meager food for the Jews who lived in the ghetto. To the right of the post office is the current town hall, which is barely visible in the photo above.

Across Langestrasse, to the west of the bus stop at the Post Office shown in the photograph above, is a block of buildings which were used as homes for Jewish children in the former ghetto. Some of the buildings in this block were also used for theater and cultural performances and building L216 in this block was the children’s library.

Buildings which were used as homes for children in the Theresienstadt ghetto (Click on photo to enlarge)

Theresienstadt building where live theater performances were held

Another building on Langestrasse, which faces the market square on the west side of the square, is today [in the year 2000] the Culture House of Terezin, shown in the photograph above. During the ghetto days, there was a theater here where live performances were given.

The rear of the Magdeburg building (Click on photo to enlarge)

The photograph above shows the rear view of the Magdeburg barracks, which is now the second Museum in Terezin; it is devoted to the artwork produced by the inmates in the ghetto. This same building was formerly used to house women prisoners when Theresienstadt was a ghetto and a transit camp.

The Magdeburg building extends from one end of the block to the other and has a series of three interior courtyards, one of which is shown in the photograph below. The Dresden barracks for women has an identical courtyard, but the Dresden building was not open to tourists when I visited.

The prisoners played soccer in the courtyard shown in the photo below.

Magdeburg courtyard (click on photo to enlarge)

The Magdeburg building was also used to house the offices of the Jewish “self government” during the ghetto days. [Dr. Benjamin Murmelstein was part of the “self government]”

The Art Museum at Terezin, which is located in the former Magdeburg barracks, shown in the photo above, is devoted to the artwork produced in the Theresienstadt ghetto.

Before World War II, the German people were considered to be the most cultured in the world. Art and music had such importance for them that they allowed cultural events in even the worst of the concentration camps, and encouraged the prisoners to create art and music in what little free time they had.

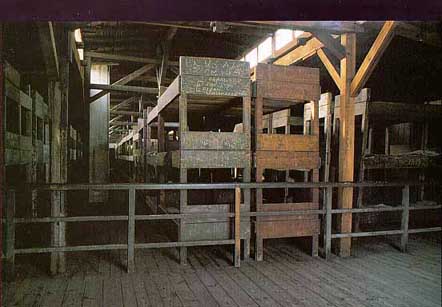

Every concentration camp had its orchestra, made up of inmate musicians, and concerts were staged even in the worst camp of all, the one at Birkenau, the Auschwitz II camp.

Typically, the camp orchestra would play classical music as the prisoners marched off to the factories to work and even as they [allegedly] marched to their deaths in the gas chamber.

During the week of cultural events in June 1944, on the occasion of the Red Cross visit, there were performances of Brundibar in the Magdeburg building.

The prisoners were allowed to do art work in the concentration camps, although not what Hitler called “degenerate” art. Hitler favored classic art or beautiful pictures, as opposed to modern art or realistic drawings depicting the horrors of the camps.

The prisoners had to hide their drawings and paintings that the Nazis didn’t approve of, but they had the courage to produce this art, even with the threat of death if they were found out.

In 1944, the Nazis discovered some of the “degenerate” artwork illicitly done in the camp, and sent the artists and their families to the Gestapo prison in the Small Fortress across the river from the ghetto. Only one of them survived the harsh conditions in the Small Fortress.

Although several of the Nazi concentration camps, such as Majdanek, Buchenwald and Auschwitz, had artists who sketched, painted or sculpted, leaving works of art which are now displayed in the museums there, the Theresienstadt ghetto was unique for the sheer volume of artwork that the prisoners produced during the war.

Taking advantage of the many famous artists who were incarcerated in Theresienstadt, the Nazis set up a drafting workshop in the ghetto where the Jews had to use their talents to produce blueprints for the Germans.

The Jewish artists in the Theresienstadt ghetto were also commissioned to do paintings for the SS headquarters.

=======

Meanwhile, what was I doing during the years that the Jews were living in luxury in Theresienstadt? Was I doing artwork, under the supervision of expert teachers? Was I playing music? Was I playing soccer in a courtyard?

NO, NO, NO, a thousand times NO. I was living in a wood frame house with no central heat and no indoor plumbing. I was sleeping on a mattress made of corn husks. I did not have an art teacher. I barely had a box of crayons. In spite of this, I do not refer to my childhood as “that time of Darkness.”